Design Thinking Model – Life Design Theory

Bill Burnett and Dave Evans 2007 – 2016

Table of Content

Introduction

The Design Thinking Model originates in the world of engineering/technology/silicon valley and can be translated to the world of career guidance/coaching and counselling. What brought me to consider this theory and to write up this page is an article by Chris Couch in Career Matters (Couch, 2025), the career guidance magazine published by the CDI, which I would really advise you to read if you are a member of the CDI, if you haven’t already.

In his article, Couch offers an excellent summary and ideas of how to work with this model with sixth form leavers, translated to the education system and the situation in the UK. I have dug a bit deeper into the origins of the theory to understand better where it’s come from and what the original theory contains.

The interaction Design Foundation website describes Design Thinking as “a non-linear, iterative [with ongoing repeated steps] process that teams use to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems and create innovative solutions to prototype and test. It is most useful to tackle ill-defined or unknown problems…” (Interaction Design Foundation, 2016). It’s a human-centred framework to navigate career decision making. Reframing is a key technique in this model and the centre thought is to challenge ‘traditional’ ways of thinking or ‘well trodden paths’. This acts as a bridge between feeling stuck and taking action.

The design thinking model originates in the world of engineering/technology/silicon valley and can be translated to the world of career guidance/coaching and counselling. What brought me to consider this theory and to write up this page is an article by Chris Couch in Career Matters (Couch, 2025), the career guidance magazine published by the CDI, which I would really advise you to read if you are a member of the CDI, if you haven’t already.

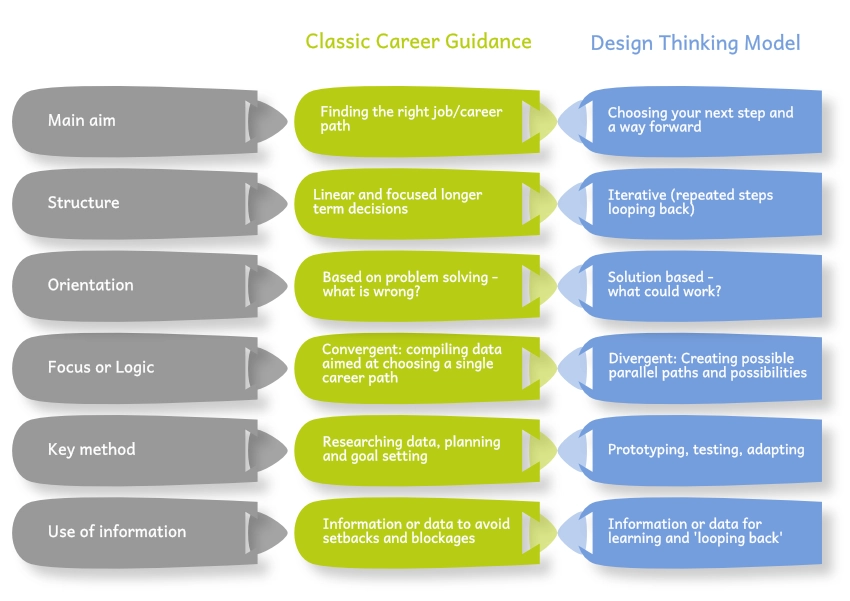

The Design Thinking Model is very different to the ‘classic’ or ‘traditional’ model of career guidance. It looks a bit as follows:

Core principles

The core principles of the model are (Burnett & Evans, 2016):

- Bias toward action: which Burnett and Evans call ‘Try Stuff’, test things out until you find what works. Progress is made through active experimentation.

- Reframing failure, dysfunctional beliefs and problems: Mistakes are viewed as critical data points for learning rather than setbacks. In other words: “reframing is essential to finding the right problems and the right solutions” (Burnett & Evans, 2016).

- Iteration: Know it’s a process and that the process is non-linear, often looping back as new insights are gained, often after mistakes are made.

- Radical Collaboration: asking for help is key in this model. Engage others; mentors, peers, and diverse people in your networks to gain fresh perspectives and “unstick” thinking.

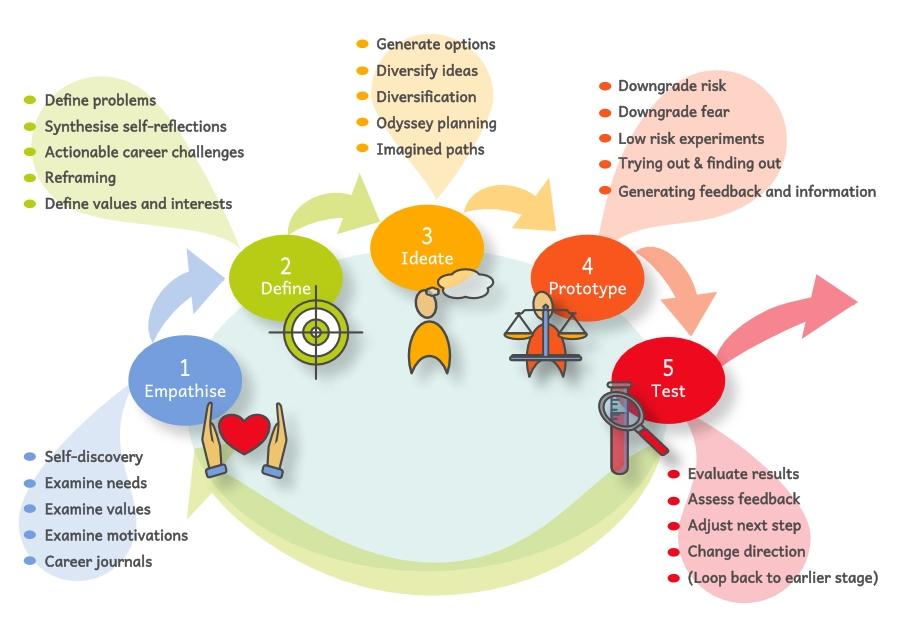

5 Key Stages

According to Stanford University, the theory consists of applying 5 key stages with the client (Stanford University, n.d.):

1. Empathize

in product design, this revolves around understanding customer/user needs. Translated to career guidance work, the focus is on self-discovery by examining your needs, values, and motivations. On the courses at Standford, suggested tools are for instance career journals to help identify what energises or drains you.

2. Define

Defining which problems you are going to solve; synthesize self-reflections into actionable “career challenges” or problem statements. The client could reframe a problem into an actionable forward looking challenge. Instead of saying “I don’t like my course,” they could reframe this as: “How can I transition onto another course that aligns with my values and interests?”.

3. Ideate

Generate a number of possible career paths without judgment. This is about diversifying, which is a key concept in the model, as opposed to converging in traditional career planning. You can use techniques like Odyssey Planning (Burnett & Evans, n.d.) to encourage the client to imagine three radically different five-year futures to break free from ingrained thought patterns:

-

- The client’s expected path: based on the trajectory the client is on now.

- The client’s alternative path: what if the present path isn’t possible anymore? Where would the client go and what direction would they take?

- The wild card path: the client’s dream scenario if nothing else was important or relevant. This is very similar to and makes me think of a technique called ‘the mystery question’.

4. Prototype

Prototyping helps to downgrade the risk and fear of making decisions and changes that feel uncomfortable. You can help the client create small scale, low-risk ‘experiments’ to test ideas. You could explore and suggest visiting employers, students taking a course, colleges, work shadowing, volunteering, etc… to test ideas and to get a taste of ‘what it is like’. Prototyping generates feedback and information.

5. Test

In this step, the intention is to use the feedback and information to evaluate the results of the client’s ‘prototypes’. Feedback or ‘information’ could be a discussion on whether the client enjoyed the task or if it met their needs or requirements or interests. You could then use this to help the client adjust their next step or direction or to loop back to earlier stages.

As you can see from the descriptions above, these steps have been translated from product design to career guidance and career support.

Couch recognises these 5 steps in his article (Couch, 2025, p. 14) and that passion isn’t discovered, but designed. Although Burnett and Evans’ description of ‘the typical intervention’ depending on someone not having ‘discovered their passion’ (Burnett & Evans, 2016, Anti Passion is Our Passion) is exaggerated, I agree with what they say here. Many of us have been in situations where we plan one thing, and several years later we find ourselves doing something completely different, being very passionate about what we do. So passion is a process, not a statement. Burnett and Evans state that passion is the cause of [making good decisions], not the other way around. So too, career planning is a process, which reminds me of quite a few other theories such as Planned Happenstance and many others. The five steps, including prototyping can help the client discover what they are ‘passionate’ about.

This is what it looks like…

Passion isn’t discovered, but designed. Finding out what you are passionate about often follows experience.

Quoting Burnett and Evans, Couch goes on to say that there are 5 different behaviours that are important to cultivate and engage in (Burnett & Evans, 2016, Disruping Life):

-

- Curiosity – Be curious – will either confirm or challenge perceptions

- Bias to action – try out stuff – will confirm or challenge assumptions

- Reframing – reframe problems as opportunities – will help see options from a different perspective

- Awareness – know it’s a process and not a static decision – will help stay vigilant of other options and ideas

- Radical collaboration – ask for help and embrace engaging others – will test assumptions and plannin

I feel these behaviours are important to keep in mind when faced with uncertainty, challenge and feeling blocked especially, but generally throughout the career management process, as this can draw out other and possibly better options, even if you are sure what direction to go into. This itself will draw the client out of ‘traditional’ career planning.

Career planning and career management are a mindset

Context and links with other theories

I bet you have some ideas of what this model overlaps with already and there are many. It will be clear, I think, that this model fits in with a narrative approach. Some of the examples of other theories that are related to the Design Thinking Model could be:

Planned Happenstance Theory – the links with this theory is clear and doesn’t need further explanation I think.

Continuous Participation Model: the continuous assessing and reassessing, keeping in mind the continuous changes in the client’s context but also the ‘looping back’ which is part of the model.

Motivation Hygiene Theory and its consideration of what causes dissatisfaction and what is motivational, especially in the context of prototyping and testing.

Boundaryless Career: seeing outside the traditional career context and taking responsibility for your own career management and development.

Careership Theory: seeing beyond your horizon; ideating and prototyping

Many other theories, including: Hope-Action Theory, Life-is-Career Theory, Motivational Interviewing, Career Engagement Model, etc…

Design Thinking in practice

Applying this model to the educational context in the UK, Couch rightly states that “design thinking gives students permission to experiment” (Couch, 2025, p. 14). Just like Krumbolz and Levin’s Planned Happenstance Theory, this model is about embracing uncertainty and ambiguity. It’s about being comfortable, or learning to be comfortable with that uncertainty and reframing it as opportunity by taking active steps to explore and question. Couch suggests his own list of actions to use the theory within a UK/sixth form context. This can of course be translated to embrace other age groups and contexts. His list of practical tools for sixth formers (Couch, 2025, pp. 14, 15) includes:

- Reframing dysfunctional beliefs and entrenched assumptions. Mirroring Couch’s examples and from my own experience:

- We’ve all come across these I’m sure; students thinking they have to go to university, especially following them taking A levels.

- “My choices determine the rest of my life and are more or less permanent”

- “Everyone else knows what they ‘they are going to be’, and I’m not”

- “ I have to know what career I am going to get into by the time I’m in Year…”

- …

- Wellbeing and engagement journal which Couch argues will help clients “track engagement and their wellbeing across different settings”. This is one I agree with, but would often expect to fail. Many of the students or young people I support feel they are really busy already. Especially in lower year groups, clients may not even be in the habit of doing their homework or they may not like ‘writing’ and be more practical. However much I agree with how important a technique this is, I would need to reframe this in a way that works for the clients, students, young people I work with. Ideally this could be through a weekly ‘catch up’ session, but the career guidance landscape in England (the UK?) is such that this is not practical. I do strongly agree that this technique is much stronger than a one off ‘psychometric test’; in inverted commas because they vary so much in quality and purpose.

- “My purpose and values”. This slightly reminds of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. To create clarity on needs, values, achievements, friendships, security and creativity, students reflect on two questions:

- “Why do I want to work?” – I would translate this question to ‘What purpose does work have in my life?’; a question that needs to go beyond the easy answer: earning money.

- “What matters most in my life?”

- “My ‘what if’ futures” – which Couch argues is based on Burnett and Evan’s Odyssey Plan model (Burnett & Evans, 2016). Also see above… Couch concludes on this point that “this narrative exercise builds agency, optimism and flexibility.

- Agency in the sense that it opens other options and that the client can own these options and has the power to make decisions about their future and next action

- Optimism: the client starts to see that there are other options out there and that they are not really stuck

- Flexibility in seeing options, other possibilities, other than those they have been told about or found out about within their ‘dysfunctional’ framework.

- “Prototyping: Mini-experiments and conversations

- We touched upon this above already as being low risk trying out of ideas, options and possibilities. Couch offers up a great list of examples (Couch, 2025, p. 15): talking with apprentices, alums and university students [which is possible through ucas and university websites], MOOCs, volunteering, job shadowing to which I would like to add, visiting universities and colleges, talking to family and friends in the job/on the course, etc… to find out as best as possible what it’s really like. It helps clients find out what they found out confirmed or challenged them, what they found surprising etc…

Couch concludes his article suggesting that these techniques can be part of an established practice. I agree wholeheartedly with this, especially once you explore how many other theories and models this overlaps with. The key point, and the key difference, is that the focus is not on students ‘finding their paths’ but designing their paths.

Students can DESIGN their career path instead of finding their career path.

Critique

I think the scope and the range of clients this can support, as well as it’s universality and application to the world of work and education at the present day makes this model important to look into further. Like Couch, I feel this can be a very powerful model to use with clients, especially those who feel they are on the wrong track or those who feel stuck. It will help them challenge their preconceived ideas and will potentially pull them out of the situation they feel they are in.

I would need to explore this further during my practice to find out the drawbacks to this theory as I struggle to find any at the moment, other than that some of my client group’s motivation may be lacking with some of the activities part of this model. Motivational techniques can go at least part of the way towards addressing this, but the situation for many, if not most sixth form students as well as those in year 11, is more complex. These students have a lot of pressures put upon them already and they don’t always have a fully developed skillset to cope with the demands they feel they have.

Of course, this is part of our role, and ironically part of the model, but working through this with clients in education takes time, and often the time we have with clients is not sufficient, equally ironically, because of the demands put upon us and the limited time we have to fulfil a myriad of demands in a cash strapped, time limited service. I am very lucky in the work I have that I can take ownership of my work to offer a high quality service, but this is not always the case.

However, I feel the key tenets of the model, especially the way in which it moves away from ‘traditional career guidance’, are crucial to up to date, 21st century career guidance.

How do you feel?

- What is the scope of the theory?

- Would you find it easy to apply to your client group and to combine with other theories?

- Which theories in your own personal tool box would you be able to combine this with?

- Also have as look at Brown’s criteria to develop a clear view and your own critique of this theory.

References

- Burnett, B. & Evans, D. (., 2026. The Magic of Odyssey Planning: Prototyping Three Futures. [Online]

Available at: https://designingyour.life/insights/the-magic-of-odysseys-prototyping-your-future-with-designing-your-life/

[Accessed 24 01 2026]. - Burnett, B. & Evans, D. J., 2016. Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-lived, Joyful Life. 1st Edition ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Burnett, B. & Evans, D., n.d. Creative Life. [Online]

Available at: https://www.creativelive.com/class/designing-your-life-how-to-build-a-well-lived-joyful-life-bill-burnett-dave-evans

[Accessed 24 01 2026]. - Couch, C., 2025. Designing Their Future: How Design Thinking can Transform Sixth Form Career Guidance. Career Matters, October, pp. 14-15.

- Interaction Design Foundation, 2016. Interaction-design.org. [Online]

Available at: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/design-thinking?srsltid=AfmBOooZX2NEEnoXQqQxUd2ZafkeMv3FZvwmyG4U_TuJ_WBJxZXQPv00

[Accessed 24 01 2026]. - Sharp Emerson, M., 2023. Applying the Principles of Design Thinking to Career Development. [Online]

Available at: https://extension.harvard.edu/blog/blog-applying-the-principles-of-design-thinking-to-career-development/

[Accessed 24 01 2026]. - Stanford University, n.d. Stanford Online. [Online]

Available at: https://online.stanford.edu/5-steps-design-your-career-using-design-thinking

[Accessed 24 01 2026].